2006

Oliva María Rubio │ An interview with Kimsooja

2006

Olivia Sand │ An Interview with Kimsooja

2006

Francesca Pasini │ An Interview with Kimsooja

To Breathe / Respirare. Palacio de Cristal. Parque del Retiro, Madrid.

To Breathe / Respirare. Palacio de Cristal. Parque del Retiro, Madrid.

An interview with Kimsooja

2006

-

Kimsooja (Taegu, Korea in 1957) is one of the most acclaimed Korean artists in the international artistic panorama. Currently, she lives and works in New York. Her works have been exhibited at biennials such as Venice, Whitney (New York), Lyon, Kwangju (Korea), as well as in the most relevant museums around the world. In our country, she has participated in important exhibitions such as Mujeres que hablan de mujeres included in the program of Fotonoviembre (Tenerife, 2001), PhotoEspaña, Valencia Biennial in 2002, MUSAC (2005), among others. She makes installations, photographs, performances, videos and site specific projects, the most recent of which was presented in Madrid's Palacio de Cristal: To Breathe: A Mirror Woman. Not long before, she had presented another site-specific project at the Teatro La Fenice in Venice. Since 1993, one of the most distinguishable elements in her work are the bottari, a kind of bundle made of traditional Korean lively colored bedcovers, which is often used for packing old clothes. Nomadism is a key subject for her, but she also tackles issues such as the relation with the other and the feminine roles, revealing not only the importance of the human being in the chaotic world we are living in but also her loneliness and fugacity.

-

Oliva María Rubio

Studying your work over time, we can say that it is a very singular work. Nevertheless, you are always dealing with present issues, such as nomadism or the relationship with the others. What are the sources of your work? -

Kimsooja

I guess the reason why my work has been engaged to present issues, regardless of a continuous singular context, is because I've been questioning old and fundamental issues on art and life. All human activities and problems come from the same root, which are old questions that have no answer, and endlessly repeat in history in one form or another. When we are planted in our own root, one can grow naturally from one's own source without trying to search another resources branches of temporary issues come out of this root in the end. -

Oliva María Rubio

Has this singularity anything to do with an education such as yours, where Asian ways of thinking are mixed with the Western philosophy Christianity, Zen Buddhism, Confucianism, Shamanism and Taoism? -

Kimsooja

In general, the complicated religious background in Korean society might confuse one's identity rather than keeping it in singular mind. It seems to be more connected with one's personality and individual history rather than social tendency. I can say that I wanted to be firmly rooted in my own culture and my own perspectives. I noticed many Korean artists in my generation were imitating and easily adopting Western practices and philosophies without question, just by reading magazines and books. At that time, in the late 80's, I decided to stop reading for almost a decade. This allowed me to question, by myself, issues on art, and to pull out ideas from my own self, rather than exterior resources. Another reason I stopped reading books was that there were so many things to read in the world besides books and magazines life and nature. My mind was always active reading all of the visible and invisible world. -

Oliva María Rubio

The bottari and the Korean traditional bedspreads with lively colours are characteristic elements of your work and have a strong presence in your installations. What do these elements represent for you? -

Kimsooja

There are two different dimensions in my use of traditional Korean bedcovers: one is the formalistic aspect as a tableau and as a potential sculpture. The other is as a dimension of body and it's destiny that embraces my personal questions as well as social, cultural and political issues. The bright colourful bedcovers that celebrate newly married couples for happiness, love, fortune, many sons and long life are contradictory symbols for life in Korean society, for a country that is going through such a transitional period: from a traditional way of life to a modern one. -

Oliva María Rubio

Despite the fact that you say you are not political matters, you have created several installations or pictures that are clearly related to political or social events, such as "Bottari Truck in Exile" (1999), presented in the 48th Biennial exhibition of Venice, or "Epitaph" (2002), a photograph taken after the September 11th attack against the World Trade Center in New York. What are the reasons for you tackle these subjects? -

Kimsooja

My practices were started solely on my personal issues and structural questions on tableau, which can be seen in the beginning of my earlier 'sewing' work and my 'wrapping' series of Bottari. However, my artwork has gradually embraced basic human problems, which have recently become a bigger part of my questions and concerns. My own vulnerability and agony on life had a presence in my earlier work, which was an important part of the healing process for me to survive. It then transformed naturally into 'compassion' for others, and turned to the healing process for others. All of my works that relate to political issues and problems originate from 'compassion for the human being', people who suffer by violence, poverty, war and injustice, which often stem from individual problems and conflicts. I would say one can categorize some of my work as a political reaction, but it is more from concern on humanity, rather than as a direct political statement as an activist. -

Oliva María Rubio

Between 1999 and 2001 you created one of your most relevant video installations, "A Needle Woman". A product of performances where you are the protagonist, always in the middle of a crowd in Tokyo, Shanghai, New Deli, New York, Mexico, Cairo, Lagos and London. For the 51st Biennial exhibition of Venice (2005) you did a new version traveling to another six cities: Patan (Nepal), Havana, Rio de Janeiro, N'Djamena (Chad), Sana'a (Yemen) and Jerusalem. Taking into account that many of these countries undergo serious problems, have you ever felt that something could happen to you? Which has been the strongest experience you have lived through while you were doing these performances? -

Kimsooja

In terms of the performance itself, the A Needle Woman performance I did in Tokyo (1999) was the strongest experience I had. It was the first performance of the series. I was walking around the city with a camera crew to find the right moment and place where I could find the energy of my own body in it. When I arrived in the Shibuya area there were hundreds of thousand of people sweeping towards me, and I was totally overwhelmed and charged by the strong energy of the crowd. I couldn't help but to stop in the middle of the street amongst the heavy traffic of pedestrians. Being overwhelmed by the energy of the crowd, I focused on my body and stood still, and felt a strong connection to my own center. At the same time, I was aware of a distinguishable separation between the crowd and my body. It was a moment of 'Zen' when a thunderbolt hit my head, as I continued to stand still there, and I decided to film the performance with my back facing the camera. During the performance there were moments I was conscious of my presence, but with the passage of time, I was able to liberate myself from the tension between the crowd and my body. Furthermore, I felt such a peaceful, fulfilling, and enlightened moment, growing with white light, brightening over the waves of people walking towards me. -

Oliva María Rubio

The first series of "A Needle Woman" was focused on encountering people in eight Metropolises around the world. The second version, made in 2005 with the same title, was focused on cities in trouble, from poverty, political injustice, colonialism, religious and political conflict in between countries and within a country, civil war, and violence. -

Kimsooja

I chose the most difficult cities in the world, although I couldn't make it to a few of the cities I wished to visit, such as 'Darfur' in Sudan, and 'Kabul' in Afghanistan. It was one of the most difficult trips I've ever experienced in my life. The difficulties with this series of performances were more about the conditions of traveling, rather than during performance time. -

When I first visited Nepal, the country was in a state of emergency, and there was no phone service in between the cities and even countries, with no internet connection during most of my stay. Foreign ambassadors were being called back to their own countries, gunshots were heard from different parts of the country while traveling, and armed soldiers were occupying every corner of the streets in Kathmandu. Even in my video, there's a scene with armed soldiers passing by. To be able to travel to Havana in Cuba, I had to travel through Jamaica, as there was no direct airline service, and no collaboration whatsoever between the US and Cuba. In Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, I went to a huge favela area called Rocinha, where I heard a series of gun shots from one mountain side to another, as if they were shooting directly from the back of me. I was standing on the roof of the central part of the area surrounded by mountains of poverty although local people considered it to be signals between the drug dealers. I also saw a number of young men carrying guns in the middle of narrow alleys to control the people in that neighbourhood. I also witnessed more poverty in N'Djamena in Chad, which is known as one of the poorest countries in the world. I witnessed conflicts between Yemen and Israel. I could only travel from Sana'a in Yemen to Jerusalem via Jordan, as there's no direct airline service in between these two countries, and the Yemeni people wouldn't allow me to enter their country if I was traveling from Israel.

-

Oliva María Rubio

When you are in these types of situations, there is no room for fear. -

Kimsooja

People believe we live in an era of globalism, which allows us to travel freely and that we are connected to anywhere in the world, but in fact, it is not true, and the world is still full of discrimination, hatred, and conflict. -

When I finished these pieces, in slow motion, they turned out to be quite similar from one city to another, regardless of the problems within. We have a very shallow perception of ourselves in terms of our notion of time, and how we perceive an extreme situation in our own time frame, but in fact, all of these cities could be seen as a similar situation in a larger perception of time.

-

Oliva María Rubio

According to works such as "A Needle Woman" or even according to the symbolism of using the bottari, travel and changing places is very present in your career, both personal and professional. Could we say that the contemporary man is a nomadic being that is forced to go from one place to another without a rest? -

Kimsooja

Although the nomadic lifestyle is a characteristic phenomena of this era, it could also be one's choice. We can still live without moving around much and be rooted in one's own place. Human curiosity and the desire for communication expands its physical dimension and happen to control human relationships and the desire of possessions, and pursuing the establishment of a global community, which includes the virtual world. But a true nomadic life wouldn't need many possessions, or control, and it doesn't need to conquer any territory; it's rather an opposite way of living from a contemporary lifestyle, with the least amount of possessions, no fear of disconnection, and being free from the desire of establishment. It is a lifestyle that is a witness of nature and life, as a kind of a process of a pilgrim. Nomadism in contemporary society seems to be motivated from the restless desire of human beings and it's follies, rather than pursuing true meaning from nomadic life. -

Oliva María Rubio

During these past years you are going for site-specific projects. You have just finished one at La Fenice Theatre in Venice, and now this one in Madrid. What is the most attractive thing about this kind of projects? -

Kimsooja

I wouldn't say site specific installation projects are more intriguing for me than other projects such as video, performance, and photos, as these were also site specific projects from my point of view. The difference is, for this type of site-specific installation, there's a solid question already existing, which I am interested in pondering. But the answer may raise another question to the audience. Other projects, such as video, performance or photos, are those I am questioning from myself, my own problems either in art practice or life, and the questioning goes both ways, to myself and to the audiences. I am interested in problems, questioning, and responding to the conditions of the site. -

Oliva María Rubio

Once having seen the results of your project for the Palacio de Cristal (Crystal Palace) in the Retiro Park in Madrid, "To Breathe: A Mirror Woman", a work that consists of an intervention in the palace [a diffraction grating film that covers all the crystal part of the building and a mirror on the ground that works as the unifier and multiplier of the space and an audio with your own breathing from the performance "The Weaving Factory" (2004)], have your expectations been met? Is the result very different from your initial idea? -

Kimsooja

Not totally, but only in terms of some technical issues. I've never used the diffraction grating film in my work before, and I'd been experimenting with its effects on a small scale model. The effect coming from the Crystal Palace, with actual sunlight, and its degree and direction, created a much more spectacular environment than from the model. I could envision the effect of the mirror floor and the effect of the sound within the Palacio de Cristal, as I had already experimented with both mirror and sound in other installations. -

Oliva María Rubio

Considering that this new project for Crystal Palace is both a logical continuation and a new step in the development of your artistic career, what does it mean for you? -

Kimsooja

From this project, I discovered 'Breathing', not only as a means of 'sewing' the moment of 'Life' and 'Death', but 'Mirroring' as a 'Breathing self' that bounces and questions in and out of our reality. Evolving the concept from my earlier 'sewing practice' into another perspective, 'Breathing' and 'Mirroring' as a continuous dialogue to my work was the most interesting achievement of a new possibility in experimenting with waves of light, sound, and mirror as a result of the space of emptiness. -

Oliva María Rubio

What is the relationship between this installation and other previous needle and sewing works? -

Kimsooja

To Breathe: A Mirror Woman is related to my earlier practices such as 'sewing', 'wrapping', and the question of 'surface', as well as the notion of 'reflection', that was always a part of my work in the metaphysical sense. Interestingly, a mirror can be another tool of 'sewing' as an 'unfolded needle' to me, as a medium that connects the self and the other self. If 'mirroring' can be a form of 'sewing the self', which means questioning the self, and connecting the self, 'breathing' is, in its dimension of action, a similar activity of 'sewing' that questions our moment of 'Life' and 'Death'. In mirroring, our gaze serves as a sewing thread that bounces back and forth, going deeply into oneself and to the other self, re connecting ourselves to its reality and fantasy. A mirror is a fabric that is sewn by our gaze, breathing in and out. -

Oliva María Rubio

What is the relationship between "A Needle Woman" and "A Mirror Woman"? -

Kimsooja

Again this goes back to the idea of surface, a continual question. A needle / body, which questions and defines the depth of fabric / surface, and a mirror that embodies the depth of body and mind, defining our existence, through a needle. I am standing as a needle to show A Needle Woman video as a mirror of the world, to question my own identity amongst others. At the same time, I am standing as a mirror that reflects the world, gazing myself from the reflected reaction the audience bounces back to me. A needle is a hermaphroditic tool that can be a subject and an object, and this theory can be applied similarly to a mirror. In that sense, I can consider a 'needle' as a 'mirror', by definition and a psychological healing tool, and a 'mirror' as a multiple and unfolded needle woven with the gaze, as a field of questions. -

Oliva María Rubio

This intervention in the Palacio de Cristal is visually very beautiful but one may even feel some kind of anguish or have the feeling that he or she is in prison. How would you explain this effect? -

Kimsooja

People may feel as if they are in my body, as the Palacio de Cristal seems to breathe, or in a cathedral bathed with stained glass, or in a space of fantasy, while walking on a mirror floor that feels like a liquid surface. Hearing my breathing and humming within the space might cause the audience to hold its breath, and they may become conscious of their own body and breathing. Maybe this feeling of being imprisoned comes from the prison of ones' own body? -

Oliva María Rubio

Inside and outside, life and death, disruption and joy, anguish and delight, uncertainty and acknowledgement, these are aspects of feelings we feel when we are inside the Palace. Why are you interested in this idea of opposites, and duality? -

Kimsooja

From the beginning of my career, back in the late 70's when I was at college, I was already intrigued by the dualities existing in the structure of the world, that are the combination of 'Yin' and 'Yang' elements. I've been looking at all existing things and the structure of the world from this perspective. An example from my earliest sewn piece Portrait of Yourself, 1983, and also The Heaven and The Earth, 1994, have vertical and horizontal elements, or a cross shape. I've been establishing my structure of perception and creation through this perspective. There was a series of assemblage based on random shapes in my work from 1990, such as Toward the Mother Earth, 1990-91, and Mind and the World, 1991, where 'duality' as 'yin' and 'yang functioned as a hidden structure. On another level of the surface, there comes another layer of yin and yang relationships, and this phenomenon goes on and on in each dimension of structure. -

But this doesn't mean that I was doing art mathematically or logically most of my works were created by the most irrational decisions and a sudden intuition rather than building up theories or logic itself, and I have always believed in the logic of sensibility within the process of creation. Duality can be one way to start understanding existences of the world, although there are so many different factors that surround and define the structure of the world. When the creation process starts, this duality theory doesn't work anymore, and it goes beyond the logic, and leads it's own life and process.

-

Oliva María Rubio

Your works aspire to capture the whole of the human experience: the body and the soul, the mind and the body are appealed to in the same extent in your creations. Why is it so important for you to make art a nothingness that experience of the body and the senses, as well as of the mind and the imagination? -

Kimsooja

Ever since I was aware of the totality of the world, I had to work on it, and it naturally involved different aspects of ways of existences, structure of metaphysics, and that of frustration and fantasy. That's what I know, what we live, and what I can express. -

Oliva María Rubio

Throughout your career, we can see that your new pieces refer to other previous works. Each of your new installations has a trace, an element, something that relates it with previous works. Do you conceive the whole of your artistic career as a kind of 'work in progress'? -

Kimsooja

For me, there is no concept of a completion. I am just moving towards a future where I find a better answer than the previous answer. This is totally against commercialism, as the art market requires a finished object to be sold and to collect. My work is still evolving and unfinished, and is just a process. -

Oliva María Rubio

And in this sense, where are you heading to? What is your ambition as an artist? -

Kimsooja

If I have an ambition as an artist, it is to consume myself to the limit where I will be extinguished. From that moment, I won't need to be an artist anymore, but to be just a self-sufficient human being, or a nothingness that is free from desire.

─ Art in Context, Summer 2006, USA, pp.24-29.

- Oliva María Rubio is an art historian, curator, and writer, who has been director of exhibitions at La Fábrica, since 2004. She was the Artistic Director of PHotoEspaña (PHE), an International Festival of Photography and Visual Arts celebrated in Madrid (2001-2003), where she programmed around 60 exhibitions. She is a member of numerous juries on art and photography, and a member of the Committee of Visual Arts “Culture 2000 programme”, European Commission, Culture, Audiovisual Policy and Sport, Brussels (2003), the Purchasing Committee at Fonds National d’Art Contemporain (FNAC), Paris 2004-2006, and artistic advisor of the Prix de Photography at Fondation HSBC pour la Photograhie, Paris, 2005. She was the curator of Kimsooja's To Breathe: A Mirror Woman at the Crystal Palace, organized by Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía in 2006.

An Interview with Kimsooja

2006

-

Kimsooja came to international fame in the 1990's following a P.S.1 residency in New York, which paved the way for one of her most famous pieces to date, Bottari Truck, a video that was subsequently shown in numerous exhibitions and biennales. Bottari Truck consisted of a truck loaded with bottari, the Korean word for bundle, and traveled throughout Korea for 11 days. The bundles were actually made of bed covers, an item accompanying the key moments of our existence from birth, marriage, sickness, to death. A Needle Woman, a video performance showing the artist from the back standing in the middle of a mainstream avenue in various cities throughout the world, further developed the concept of sewing towards abstraction bringing together people, cultures and civilizations. In a subtle way Kimsooja (b. 1957 in Korea), who works primarily in video, performance, installation, and photography has advanced to a premier artist in her discipline taking up sensitive issues like migration, integration or poverty. Besides taking us on her journey, Kimsooja's work is an invitation to question our existence, and the major challenges we are facing. In the interview below, she looks back at the past decade, and discusses her latest projects and undertakings. Olivia Sand reports.

-

Olivia Sand

Certain pieces you completed are seminal pieces (see above), and have toured numerous biennales and museums over past years. What mikes these pieces so important and why do you think people feel attracted to them? -

Kimsooja

The formal and the aesthetic aspects may draw people to these pieces, but I believe their success is also based on their content and the topics they address. Today, it seems that we are witnessing a 'cultural war' with many, issues arising in a global context bringing together different races and beliefs with an increasing discrepancy between rich and poor, economically powerful and less powerful countries. Needless to say, the present power structure causes many problems and disasters around the world. The issues that I address in Bottari Truck and A Needle Woman are very much related to current topics, such as migration, refugees, war, cultural conflict, and different identities. I think people are interested in considering these topics through the reality of the work; this may be one reason for their success. In addition, the aesthetics and some elements of the form in A Needle Woman, for example, are things with which people can identify. The piece demonstrates a different approach towards performance compared to what has been done in performance so far. It is a different format and a different perspective from a 'classical' performance, where the artist is 'doing' an action. I believe that you can connect people and bring them together to question our condition without aggressive actions. -

Olivia Sand

You learnt to sew with your family. Is sewing actually the element that led you to pursue an artistic career, ultimately serving as a means of expression, which remains to this day in your work? -

Kimsooja

Definitely. The practice and my concept of sewing represent the constant basis of all of my work, from the beginning until today. The concept of sewing is always redefined, redeveloped and regenerated in different forms. After sewing pieces on the wall, or the Bottari pieces, which represent another way of three-dimensional sewing, I began to connect the relationship between people, my body, and another way — actually an invisible way — of sewing, like weaving the fabric of society and culture for example. My practice of sewing is always evolving, generating new ideas to redefine concepts. -

Olivia Sand

You recently started a website, www.kimsooja.com. While presenting the site, you come to the conclusion that 'a one word name is an anarchist's name'. What do you mean by that? -

Kimsooja

I do not think of myself as an anarchist with any critical political meaning. I see myself as a completely independent person, independent from any belief, country, or religious background. I want to stand as a free individual, who is open to the world. -

I had thought about starting a website for some time, but I was reluctant to do so because of the commercial aspect linked to such an undertaking. One day, however, I decided to move forward, and I began to carefully think about a website address. With the rapid growth of the internet, an email address is the key to getting access to the world to a universe without boundaries. I wanted to present myself as a free individual from any connotations (which exist around a name — the affiliation through marriage, for example), but not as an aggressive anarchist activist trying to change the world.

-

Olivia Sand

On your website you talk about 'twisted information', and your desire to promote ideas that have not been given the importance they deserve. To what are you referring? -

Kimsooja

I realize that the media cannot be objective towards all the topics they cover, and personal points of view and experiences are also of great importance in the way the news is presented. However, I frequently witnessed how the media failed to acknowledge the relevance of an artist, which also resulted in ignoring or misunderstanding some of their existing art works. Through the website, which I launched in 2003, my goal was to open a forum for people to communicate openly and honestly about the art world, and the world in general. I am aware that it is a very modest undertaking, but I nevertheless wanted to offer a place where people could share their thoughts. All too often, people find themselves in a situation where they have no power, where they are manipulated, and they have no means to access or reveal the truth. So far, there have not been many people from the curatorial side, but there are many ordinary people, and a few artists, who use the site. -

Olivia Sand

It seems that people are used to getting distorted information... -

Kimsooja

In a certain way, yes. I think this can mainly be attributed to the fact that whatever is written becomes true, and people tend to believe whatever is written. I just want to provide a forum for people who want to speak up. -

Olivia Sand

It seems that we are living in a strange time: never has the access to information been so great and the sources so diverse, but a lot of people just seem to be getting and relying in 'distorted' information. Do you agree? -

Kimsooja

We just need to consider our domestic television networks (in the US), which provide very little information on foreign countries, on their view and response regarding the status of America in the world today. One needs to rely on the European and Asian channels to get a better awareness of what is going on in the world. As an artist, there is always a dilemma: should an artist take action following certain political decisions or should an artist stay away from politics? In my case, I want to open the floor for people to discuss and exchange ideas. In a way, I am a witness and I am not making any direct comments or statements. I do not see my role as to judge people, but rather as to raise awareness about certain topics. The response will be in the hands of each individual. -

Olivia Sand

Do you feel that today artist have the power to set things in motion? -

Kimsooja

Yes and no. Yes, artists could set things in motion, and can be very 'loud', but artists do not have enough power to persuade people to change the world. However, we are responsible for our own example and how we perform them. It is not necessary to make political statements, for example, but we can make a statement in a beautiful, peaceful, and spiritual way. In my opinion, artists can do something to resolve certain problems, but it is not easy, and it tends to remain a modest attempt of a very different scale than the head of a political section. Within a few seconds, they can give instructions to empower certain people, yet take it away from others. As modest as our attempt may he, I think it is important to bring attention to the suffering and death caused by unconditional unfairness. We cannot just neglect that. -

Olivia Sand

Nam June Paik passed away at the beginning of this year. Do you feel that in terms of contemporary art, he has left a legacy behind in Korea? -

Kimsooja

Absolutely. Before the 1988 Olympic Games in Seoul, he had no presence in Korea, nobody knew him except for some art insiders, and none of his works were shown. Although since 1988 things have changed dramatically, and Nam June Paik has been widely seen in Korea, still I do not think he received enough recognition or support from the Korean government. Throughout his career, he did a lot for Korea, and for the Korean people. He was very influential on Korean artists, and he contributed to creating a good image of Korea. He should have been more appreciated and supported by Korea, the Korean people, and by Korean museums. However, I am glad that ultimately the county where Nam June Paik was born has decided to build a museum dedicated to his work. The county has been acquiring hundreds of his pieces, and I consider it a great gesture — all the more so as it is based on the initiative of a provincial political officer and not a museum. This is very encouraging, as the museum will permanently be dedicated to Nam June Paik. -

Olivia Sand

Has Nam June Paik changed the attitude of museums in Korea, encouraging them to collect the work of contemporary Korean artist like you, who are mainly working in video and performance? -

Kimsooja

Presently, only one of my pieces is in a Korean museum: A Needle Woman, which belongs to the Samsung Museum. This specific piece caused many difficulties when the museum decided to acquire it, as my video piece was purchased by the museum, the Korean government charged considerable tax on it because it was considered a commercial movie. Consequently, the Samsung Museum and the Korean tax customs were in a lawsuit for many years. Korean law makes no differentiation between contemporary art works like my video pieces and a mass production commercial movie. Ironically, the tax authorities believed my video work was similar to Nam June Paik's work, which is considered the father of video art. The museum finally won the lawsuit last year, but it took over five years to settle the dispute. My case set a precedent, and today, artists can sell their video pieces without paying these enormous taxes. So far, A Needle Woman remains the only piece from my work in a museum collection in Korea. -

Olivia Sand

What is the reason for your 'under representation' in museum collections in Korea? -

Kimsooja

It is difficult to say. Perhaps it has a lot to do with the way the system (the galleries, the museums etc.) work, or perhaps they simply do not like my work. -

Olivia Sand

Is your work widely represented in American museums? -

Kimsooja

My work is represented in some American museums (P.S.1, some West Coast museums, etc.), but most of my projects are actually taking place in Europe. -

Olivia Sand

Do you think your work is 'too different' for an American audience? -

Kimsooja

I think the perception on art is very different in America and in Europe. If we take a closer look at the gallery scene in New York, most of the shows taking place in Chelsea are based on 'products' and people buy these 'products' rather than artworks that inspire them. I think the materialistic perception and the environment in the US clearly influence the collectors and their taste. There are always some exceptions, but I personally tend to find European audiences more sensitive, often more knowledgeable, and perceptive. -

Olivia Sand

You presently have a show in Madrid that runs until July. Can you describe the piece? -

Kimsooja

The exhibition is at the Crystal Palace, which is run by Reina Sofía. It is a beautiful glass pavilion, and I decided to create one large single installation. I covered the whole glass pavilion with a diffraction grid film, which creates a rainbow like effect all over the surface. The effect varies quite dramatically over the glass depending on the light source, the direction of the light, and its sharpness. In addition, there is a mirror structure over the floor, which reflects the entire structure of the building below the feet of the audience. I also installed the Weaving Factory, which I previously showed in Venice. -

Olivia Sand

How would you say your work has evolved since your residency at P.S.1 in New York? -

Kimsooja

For me, P.S.1 was one of the most influential experiences: it opened my career to the international art world. It led me to create my Bottari piece, and I started to do more installations based on my work from P.S.1. When I went back after a stay abroad, I became aware of the cultural conflicts within Korean society because by that time, I had the experience that things could be different. I had even more difficulties after coming back following a one year and a half stay in New York. I had to struggle because I had different perspectives, while the society was still very closed, stressful, and not supportive. I decided to leave the country to settle in New York, which was difficult, but at the same time very challenging. Putting myself on the edge of my life was a great challenge, and in retrospect, I think it made my professional practice even more focused, and more in depth. Since then, everything has been positive with museum shows around the world, participation in the most prestigious international shows and biennales, and good reviews. -

Olivia Sand

Has religion, Buddhism, had an impact on your projects? -

Kimsooja

I am not a practicing Buddhist, but I am very interested in Buddhism. It is very similar to the way I am thinking and to the way I perceive life, death, and daily life. I believe it carries great truth, but I do not want to represent any specific religious belief. I want to go beyond that, and embrace everyone's beliefs. -

Olivia Sand

Which projects are closest to your heart? -

Kimsooja

The sewing piece, the Bottari piece, and, of course, A Needle Woman. The Lighthouse Woman was also one of my favorite projects, in part because it was temporary and site specific with a very special environment and collaboration. I am strongly drawn to the idea of completing additional site specific and temporary installations, especially in Europe, where there are numerous very interesting sites.

─ Asian Art Newspaper, May 2006, pp.2-6.

- Olivia Sand is a correspondent for the Asian Art Newspaper based in New York, and Strasbourg, France. She contributes to The Asian Art Newspaper on a monthly basis, covering the Asian contemporary art scene. The newspaper, published out of London, serves as a thorough information source on the world of Asian art.

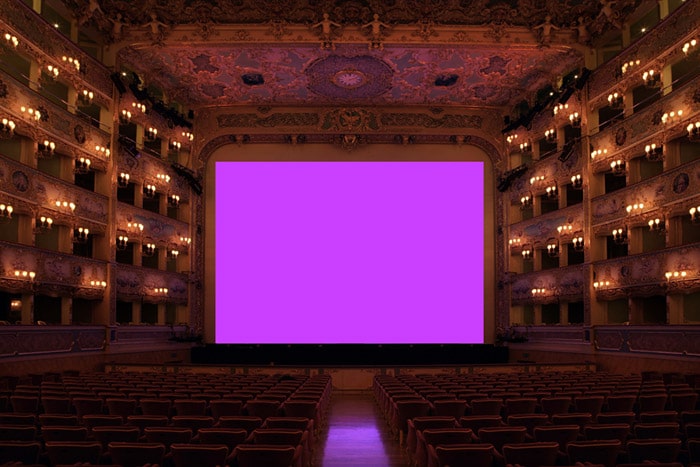

To Breathe / Respirare, 2006, Teatro La Fenice, Venice.

To Breathe / Respirare, 2006, Teatro La Fenice, Venice.

An Interview with Kimsooja

2006

-

Francesca Pasini

Space, light and the body are the elements with which you give form to the world. In all your works the purity of the images might seem to situate the vision in metaphysical space, but you accomplish this in the physical dimension. -

Kimsooja

Physical and metaphysical states coexist simultaneously as one, rather than as separate or parallel entities. Physicality represents the metaphysical, in the similar state of space as time, and time as space, I believe. -

Francesca Pasini

How important is the idea of the "void" in your process of "making space"? -

Kimsooja

For me, making space means creating a different space, rather than "making" a new one. The space is always there in a certain form and fluidity, which can be transformed into a completely different substance. For example, our brain cells or mental space construct a physical and visual tableau, sculpture, or environment, which are transformed spaces. My interest in "void" is as a negative space in relationship to "Yin" and "Yang," as a way of inhaling and exhaling, which is the natural process of "breathing" as a rule of living. This idea of duality can be found in all of my working methods from the beginning of my practice. -

Francesca Pasini

In the audio work The Weaving Factory, which accompanies the projection presented on the screen at the Theater La Fenice in Venice, what is the link between the "breathing" that comes from the color spectrum, versus the one that is created by your breathing? -

Kimsooja

The breathing element in my video projection To Breathe: Invisible Mirror / Invisible Needle is based on the abstract of the phenomena of nature, which was generated by a digital color spectrum. This creates a clear distinction from the video pieces I've shown at Fondazione Bevilacqua La Masa, which are captured from the existing phenomena within nature, as part of my study on nature. The sound for the vocal performance for The Weaving Factory was made from my own breathing at different speeds and depth, and humming different notes through my nose and, in the end, by opening and closing my mouth. Both audio and visual breathing is performed within the body of La Fenice Theater, which I took as my own body, which breathes in and out, connecting the bodies of the audience to that of the theater. It was also interesting to relate the nature of the lyrical theater, which is all about singing, which in turn, is breathing. -

Francesca Pasini

In your current project at Palacio de Cristal in Madrid, you also use the same combination of color and breathing "to make space." -

Kimsooja

The glass pavilion is covered with translucent diffraction film, that diffuses the light coming through the structure into rainbow spectrums, which is then reflected by the mirrored floor, while the breathing from the audio piece The Weaving Factory fills the space, bouncing back and forth onto the mirror. The waves of light and sound, and that of the mirror, breathe and interweave together with the viewers' bodies within the space. -

Francesca Pasini

What kind of relationship is there with the project in Venice? -

Kimsooja

Both To Breathe: Invisible Mirror / Invisible Needle and To Breathe: A Mirror Woman are related in terms of the notion of "surface", "sewing", and "wrapping". Interestingly, a mirror is another tool for sewing, as an "unfolded needle," that connects the self and the other self. Mirroring is sewing and to sew is, in the end, to breathe. -

Francesca Pasini

I see a progression with respect to your previous works. To an increasing extent, the visible loses its perspective limits: in Bottari - Throwing the globe, as well as in A Wind Woman, we have the perception of colors' movement without any distinct image; meanwhile, in To Breathe: Invisible Mirror / Invisible Needle we have only a color spectrum. -

Kimsooja

Most of the videos I showed at Fondazione Bevilacqua La Masa are entitled "Bottari...". The word "Bottari" means "bundle" in Korean. A Bottari is wrapped fabric that contains daily objects, for carrying one's belongings and moving households. It is the easiest and simplest way to locate and dislocate one's belongings. When Koreans say, "Wrap the bundle," and Westerners say "Wrap it up," it means, finish the relationship or move on. But when it is used by women in a specific way in Korea, it means she is "leaving her own husband and family to pursue her own life." In the series of those videos with subtitles, I applied the general meaning of Bottari as a wrapped image rather than focusing on the feminist connotation. The works at Fondazione Bevilaqua La Masa in Venice are studies on nature where the boundaries are ambiguous and continuous, except for the frame of the video. Especially in To Breathe: Invisible Mirror / Invisible Needle, there seems to be no surface that remains in our gaze as the color spectrum light from the projection is constantly changing and transforming from one color into another, so there is no definition of surface in this "painting." My motivation for creating this piece was to question the depth of the surface, as well as questioning its definition, and this has been one of my constant themes since the sewing pieces earlier in my career. Where is the surface? What in the world is there between things? -

Francesca Pasini

And the distance between what we see, and what we perceive, is it important? You mentioned your sewing pieces, could you explain the development in relation to the videos? -

Kimsooja

My work is based in part on questions of perception — it can be found continually in my practice. In making art, I am particularly interested in getting close to the most accurate answer to the questions on the relationship and reality of things and life. I started working in video in 1994 from my interest in its "frame" as a means of "wrapping," rather than focusing on the image-making quality of the video. In the context that "wrapping" is, in fact, three dimensional sewing, it is all connected and influenced by the notion of "sewing" and "wrapping", in which the camera lens plays the part of the needle's eye. -

Francesca Pasini

In other videos at Fondazione Bevilacqua La Masa, such as Bottari -Waiting for the Sunrise, as well as in Bottari - Chasing the fog, or in Bottari - Drawing the Snow, the viewer must wait in front of an image that changes very slowly, and in doing so, captures the perception of time itself, inside a sort of immobility. Does the concept of time take on the function of an emotional state? -

Kimsooja

The immobility of the audience's body occurs while watching what is taking place in the video, and its relationship to the passage of time. The body of the video camera and the body of the audience take on the same barometric role, to measure and capture the passage of time. Our waves of emotion and perception of the video move along with the transition of time and the changing landscape within the video. -

Time exists in our minds only when we are conscious of what we think, feel or act. To percieve what we see, we need to focus on moments that extend the duration of time with our own consciousness.

─Tema Celeste, Vol. 166. July/August 2006, Milan, Italy, pp. 50-55.

- Francesca Pasini is a Milan-based art critic and independent curator. She contributes to Artforum, Tema Celeste, Flash Art and Linus; has written essays for the exhibition catalogues of Italian and international artists. She has curated numerous group and solo shows in private galleries and museums, including Castello Di Rivoli, Museo d'Arte Contemporanea, Rivoli-Turin; Mart — Museo d'Arte Moderna e Contemporanea of Trento e Rovereto; PAC Padiglione d'Arte Contemporanea, Milan; Fondazione Bevilacqua La Masa, Venice; Teatro La Fenice, Venice. For the 1993 Venice Biennial she curated the international exhibition, Voyage to Cythera. She is the artistic director of Fondazione Pier Luigi e Natalina Remotti, Camogli, Genoa.